Impact of watching live performance on the brain revealed

Primary page content

A new study has revealed that watching live performances in a group setting impacts brain activity, with performers breaking the fourth wall especially causing synchrony.

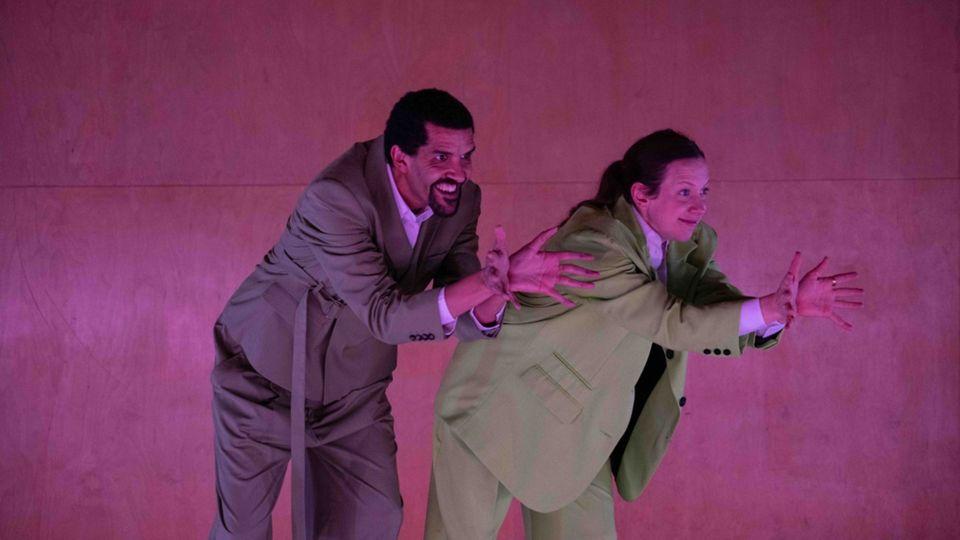

Seke Chimutengwende and Stephanie McMann in Detective Work. Credit: Hugo Glendinning

A study published in iScience has captured the impact of watching live performance in a group on the brain. When people watched a live contemporary dance performance, their brainwaves synced up, signaling shared focus and attention. But that synchrony dropped when the same performance was viewed alone on video.

The study is part of the NEUROLIVE project, a collaboration between scientists and artists at Goldsmiths, University of London, University College London, the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics and Siobhan Davies Studios. It is a 5-year £1.6m European Research Council funded interdisciplinary project investigating the question of what makes live performances special.

Professor Jamie Ward from the Department of Computing, who led the work on wearable technology, Haeeun Lee, Associate Lecturer in the Department of Psychology, and Sonia Abad-Hernando, Post doctoral researcher in Pscyhology, are part of the team of authors. Professor Ward’s dual background in wearable technology and theatre inspired many of the technical innovations used in the NEUROLIVE project.

Measuring the impact of live performance on brain synchrony

During a performance of contemporary dance piece ‘Detective Work’, choreographed by Seke Chimutengwende in collaboration with dance artist Stephanie McMann, electroencephalogram (EEG) headsets were used to track the brainwaves of 59 audience members. The brain synchrony was then compared with other participants who watched a recording of the same piece in the cinema with others, or alone in a lab.

The uniqueness of this project is its success at combining performance art with neuroscience and technology – and generating valuable contributions towards all three areas.

Professor Jamie Ward

During the live shows, audience members’ brains synced in the Delta band – a range of slow frequency brainwaves typically associated with mind-wandering and social processing. When the performers made direct eye contact with the crowd, the synchrony was especially strong.

Watching the recorded performance with others in a cinema still triggered brain synchrony, but for those watching alone in a lab, the synchrony weakened. This suggests that sharing the experience with others, or “social liveness,” may be as important as the performance itself.

The research team fit a participant with an EEG cap before the performance. The equipment monitors brainwave patterns to understand how live performances affect audience members.

“The fact that we find synchrony in the Delta band links the experience of live dance to the idea that performing arts are social art forms,” says project lead Dr Guido Orgs, Associate Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London. “They are created by performers and an audience who are in the same space at the same time.”

To investigate whether moments of heightened engagement could be predicted, the researchers asked choreographer Seke Chimutengwende which scenes he expected to be most engaging. Synchrony peaked at nearly every moment he had predicted.

“There’s so much knowledge contained in live performance,” says co-author Matthias Sperling, artistic director and researcher at NEUROLIVE. “The artists are experts in liveness, and so are the audience. This research offers a new way to tell stories about what’s happening in that rich, complex environment, using science to open a different window into those shared experiences.”